MLUI / Articles from 1995 to 2012 / Traverse City Eyes Cooling Agreement

Traverse City Eyes Cooling Agreement

Will town become Michigan’s seventh to tackle global warming?

November 12, 2006 | By Carolyn Kelly

Great Lakes Bulletin News Service

| |

| NASA | |

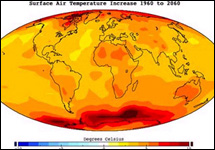

| A computer model developed by NASA using satellite observations predicts where and how quickly the earth will warm if greenhouse gases emissions remain unchecked. |

TRAVERSE CITY—A booming national campaign that is pushing American cities to tackle global warming rolls into this northern Michigan town tomorrow evening.

The three local groups introducing the campaign here hope to draw a large crowd to a Traverse City Commission study session scheduled for Monday night, Nov. 13, at 6 p.m., at the Government Center, on Boardman Avenue. The session will begin the formal process of considering whether Traverse City should join the campaign, known formally as the U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement.

The local nonprofit organizations—the Sierra Club, the Northern Michigan Environmental Action Council, and the Institute for Sustainable Living, Art & Natural Design—want the commission to adopt the agreement and pledge to reduce the city’s own emissions of heat-trapping “greenhouse” gases, which scientists say are warming the atmosphere and changing the climate in hard-to-predict and potentially dangerous ways.

If Traverse City signs the climate protection agreement, it will be the seventh Michigan municipality to pledge to reduce greenhouse emissions to seven percent below 1990 levels—the goal specified for the United States by the Kyoto Accords. America initialed the international treaty in 1998, never ratified it, and completely rejected it after President George W. Bush took office, in 2001. All other major industrialized countries except Australia have ratified Kyoto, which took effect in February of 2005.

Traverse City’s assent would also mark the continued growth of a movement that has gained signatures from 339 American cities in 46 states in less than two years. Adopting it essentially requires towns to use energy far more efficiently, purchase at least some of it from sources other than coal and natural gas, and use transportation that requires less gasoline and diesel.

Some “green” economic experts say that an aggressive attack on climate change presents Michigan with a clear choice: If the state continues to depend on development that favors low-mileage car and truck manufacturing, sprawling land use, outdated building efficiency, and fossil-fueled energy generation, it will become a permanent economic backwater.

But, those experts say, if Michigan instead embraces efficiency, compact development, public transit, and alternative energy sources such as wind turbines and solar cells, it could prosper. A firm decision to move toward a "sustainable" economy, they say, would unleash the research capacities of Michigan's large universities, revive its crumbling industrial base, and make it a leader in new technology and land use policies.

So far, six Michigan cities—Ann Arbor, Grand Rapids, Ferndale, Marquette, Berkley, and Southfield—have signed the climate agreement. Observers say that, in particular, Ann Arbor and Grand Rapids are pointedly challenging both a recalcitrant federal government and the state, which regulates power companies, finances Michigan’s sprawling development, and has done little to combat global warming. They add that both towns are using climate protection strategies to save taxpayer dollars and facilite economic growth.

Ann Arbor Leads the Way

Leading the charge is Ann Arbor, which began working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in 1997, when it joined Cities for Climate Protection, a project of the International Council of Local Environmental Initiatives. The city has long used economic arguments to justify its climate protection measures.

City officials say their most dramatic example of climate protection is at their municipal landfill, where a project pays for itself by allowing a private company to capture and “digest” methane from the landfill, convert it to electricity, and sell it for a profit. The city claims that the project now annually eliminates the same amount of greenhouse gas emissions that 4,000 cars would spew annually into the atmosphere, yet generates electricity to power 1,000 homes.

The city is recycling and composting over 50 percent of its solid waste, according to Mayor John Hieftje, who served as the Chair of Recycle Ann Arbor before becoming mayor. Those efforts represent Ann Arbor’s second-largest reduction in greenhouse gas; in effect the program keeps another 2,400 cars off the road while paying for itself.

The city also invests heavily in energy conservation methods that recover their initial costs and finance further conservation efforts. They range from requiring employees to shut off idling engines, to keeping drafty windows well caulked, to installing compact fluorescent light bulbs that consume two-thirds less energy than standard bulbs and last up to 10 times longer. The town is switching its traffic lights to new, ultra-efficient LED (light emitting diode) bulbs; while the new bulbs are costly, they also save large amounts of energy.

“Conservation of energy has saved millions of dollars over the past fifteen years,” said Mayor Hieftje.

Efficiency and Renewable Energy

Ann Arbor is also embracing a policy that is common in some other states but still faces resistance in some quarters of Michigan industry and government. Known as renewable energy portfolio standards, the policy requires the city to obtain a certain percent of its electricity from renewable sources such as wind turbines, solar sells, and bio-energy by 2010. In Ann Arbor’s case, the requirement is 30 percent by 2010. The city also wants residents to purchase 20 percent of their power from renewable sources by 2015.

David Konkle, the City of Ann Arbor’s longtime energy coordinator and a widely recognized expert on renewable energy and energy efficiency, points out that energy efficiency and portfolio standards work hand-in-hand: If a city or a household uses less energy, it takes fewer wind turbines, solar panels, or other renewable sources to meet the renewable goals.

Ann Arbor has modified its fleet of city vehicles to run on 50 percent bio-diesel, a renewable fuel, during the summer, in order to rely more heavily on Midwestern farmers and less heavily on foreign oil. Mayor Hieftje even suggests that Ann Arbor could grow some of its own fuel in the greenbelt that the city is assembling around its borders; he argues that this is good for the local economy and national security.

“In an emergency—war in the Middle East, a hurricane that disrupts oil refineries—we could power many of the basic city services on locally grown fuels,” Mr. Hieftje said. “Having control over the fuel in your own economy is not only an environmental message, a cost saving message, but one of security.”

The mayor and his staff say they are eager to buy Michigan wind energy, which would replace coal power, for economic as well as environmental reasons.

“We really want to bring wind energy to Ann Arbor,” according to the mayor, and “spur the development of wind energy in Michigan. We feel that’s vital not just to us—but to the economy and vitality of the state. We currently import most of our energy, which means we’re sending money outside the state.”

So far, though, Ann Arbor’s efforts to buy Michigan wind power have been stymied by delays in constructing in-state wind farms. The city has been negotiating with wind developers Noble Environmental Power and Mackinaw Power, as well as with DTE Energy, which operates many large coal plants, for years and hopes to someday sign a 20-year wind energy contract. But until Michigan, the nation’s 14th-windiest state, gets more than its current three large turbines spinning, Ann Arbor will continue to send its money to other states to buy green energy credits, according to Mr. Konkle.

Grand Rapids: Green Business

Given Ann Arbor’s head start and aggressive approach to reducing greenhouse gases, Michigan’s second-largest city, Grand Rapids, has some catching up to do. In the past few years, however, the city has taken some big strides. The measures, officials there say, are also designed to boost economic development.

The city recently pledge to buy 20 percent of its power from renewables by 2008. Mayor George Heartwell believes that Grand Rapids, with its long history of manufacturing, could build turbines for wind energy facilities in Michigan and the nation. Indeed, a mature American wind industry could generate more than 8,000 jobs in Michigan, according to a September 2004 study conducted by the Renewable Energy Policy Project, a Washington-based alternative energy advocacy group.

Manufacturing turbines would fit Grand Rapids’ overall development strategy of growing clean, green, innovative businesses that provide good jobs and enhance quality of life. The city is already a hub for biotechnology research, and entrepreneurs are also pushing to bring development of new water management technology to their city.

One area where Grand Rapids clearly leads the state is in highly efficient “green” buildings. The U.S. Green Building Council has awarded a remarkable 11 percent of its LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certifications to buildings in Grand Rapids. LEED-certified green buildings have superior indoor air quality, use environmentally responsible materials, save water, and are highly energy efficient—slashing utility bills and greenhouse gas emissions. The city promises its new municipal buildings will be LEED-certified.

Grand Rapids is extending LEED into its neighborhoods, too. The city’s new zoning code will encourage compact, walkable neighborhoods, spur in-town development that’s close to transit, encourage the redevelopment of old buildings, and discourage sprawl. By carefully incorporating the principles of Smart Growth and LEED-ND (as in Neighborhood Design), the ordinance will make it much easier for developers to build LEED-certified neighborhoods and gain a hip, green marketing edge.

The new ordinances will also reduce warming emissions associated with transportation. As more people live close to work, school, and shopping, and as more neighborhoods are equipped with sidewalks, bike facilities, and transit, people can drive less, and walk and bike more. The city’s leaders say that the new code, coupled with Grand Rapids’ commitment to improving its waterfront, expanding transit, and offering wireless Internet access, will attract the talented graduates and entrepreneurs needed to expand the city’s knowledge-based economy.

Carolyn Kelly is the Michigan Land Use Institute’s associate editor. Reach her at carolyn@mlui.org. Tomorrow night’s meeting is at the Traverse City Government Center on Boardman Ave. at 6 p.m.

_______________________________

Update: The city commissioners unanimously voted to authortize mayor Linda Smyka to sign the U.S. Mayor's Climate Protection agreement at the Jan. 15, 2007 meeting. They also authorized city manager Richard Lewis to move forward with a greenhouse gas inventory, which will enable the community to measure the results of its efforts. Stayed tuned for more information.