MLUI / Articles from 1995 to 2012 / After Calamity, New Yorkers Sought Traditional, Intimate Public Places

After Calamity, New Yorkers Sought Traditional, Intimate Public Places

One lesson from terror attack: people avoided modern, out of scale development

October 24, 2001 |

Great Lakes Bulletin News Service

| |

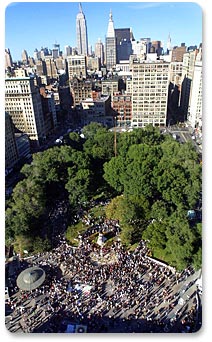

| Four days after the attack on the World Trade Center, a time of the city's greatest need, people gathered for a memorial service in Union Square Park. Such places are the secret of New York City’s resilience, and the heart of the spirit that has the world in awe. |

In fear, New Yorkers don't retreat in isolation behind gates and high fences. They seek face-to-face contact. They congregate in impromptu ways. This is one of the hallmarks of a more traditional and far more flexible and vibrant pattern of development. Call it the Old Urbanism. Now as New York springs back, it is proving again the value of Old Urbanism and why it endures.

As America responds to the terrorist attack and considers its full meaning, one lesson that can already be drawn is how the design of New York city’s traditional neighborhoods and intimate public spaces helped to serve a very human need to be together. This lesson is in sharp contrast to the sprawling, wasteful, and out of scale patterns of development that have dominated suburban and city design for half a century and which have the effect of keeping people apart. Moreover, as citizens, public officials, and architects ponder replacing the Twin Towers, it is already clear that a smaller, more intimate, more human-scale design will almost certainly prevail.

Though too much of New York City has been turned over to suburban malls, isolating office complexes, and suburban housing developments, most of New York City nevertheless remains a world class model of Old Urbanism. It is the secret of the city’s resilience, the reason for its endurance, and the heart of the spirit that has the world in awe after such a calamity.

Times Square, for instance, no longer represents the Old Urbanism with its new mall stores, overstuffed office towers, and formula hotels. The historic theaters are the only thing left that is truly New York and even they, like Times Square itself, need a scheduled event to bring people together.

The perfect contrast is Union Square Park, on 14th Street between Broadway and Park Avenue, where so many New Yorkers gathered after the disaster. Thirty years ago, Union Square Park was given up for lost, badly reconfigured to discourage easy access, and overtaken by petty criminals. Then the first Greenmarket opened in 1976, despite official skepticism and resistance.

The Greenmarket, of which there are now more than two dozen around the city, was an innovation of the best kind and remains a national model. The Greenmarket was the catalyst for rejuvenation of this downtrodden neighborhood by bringing a cross section of people to mix and mingle in old urban ways. It attracted first-class restaurants thrilled to have easy access to fresh produce. Lastly, it stimulated the upgrading of so many existing buildings for residential and commercial use and a redesign of the park to make it an even more pedestrian-friendly place. Union Square Park is now is the heart of Silicon Alley, the home and workplace for a generation of young people that might have been lost to the city.

And so at the time of the city's greatest need, people gathered in Union Square Park. Some came just to be in a public place, to express rage or to display their patriotism. A statue of George Washington served as a shrine where candles, flowers, photos, and notes could be left in honor and in memory of those lost.

Nobody except the terrorists could have predicted that the World Trade Center would become the tomb for 5,000 people. But well before the attack, the Twin Towers were widely viewed as the city's backdrop, not its heart. To many New Yorkers, those buildings were inhuman in scale and unpleasant to visit or work in. Nevertheless, their minimalist, box-like form dominated the skyline, overpowering the Empire State, Chrysler, and Woolworth buildings — the truly great skyscrapers.

In time the site of the World Trade Center will be rebuilt. What architectural form takes hold will be debated. But it won’t be nearly the same. For sure it will not be seven buildings on top of a shopping mall that tries to create a public space on the second floor. Open spaces don't become public places unless they are at street level and provide the passerby with easy pedestrian access.

The World Trade Center represented the power to build big. Without the towers, New York's skyline returns to being a celebration of the ingenuity, entrepreneurship, and individuality that is this city's greatest asset. But it also raises a new question about our civilization’s design that is fit for the 21st century. Is there really lasting value in building big just to prove that we can?

Roberta Brandes Gratz, an international lecturer on urban development issues and a former reporter for the New York Post, is the author of "The Living City: Thinking Small in a Big Way," and "Cities Back from the Edge: New Life for Downtown." She lives in New York City and can be reached at LIVINGCITY@aol.com. For other penetrating commentary on sprawl, urban design, and land use policy by the Elm Street Writers Group please see: http://www.mlui.org/projects/growthmanagement

/elmstreet/elmstreetintro.html