Clean Energy / News & Views / Articles from 1995 to 2012 / Coast to Coast, Farmland Preservation Blossoms

Coast to Coast, Farmland Preservation Blossoms

Farmers, voters join hands to strengthen industry, communities

August 11, 2006 | By Keith Schneider

Great Lakes Bulletin News Service

First of three parts LOWELL, Mich.—As it happened, the rain stopped on the morning of May 15, 2006 just before a caravan of late-model vehicles dropped a swirl of local dignitaries—including a state senator, one of Michigan’s wealthiest philanthropists, and two TV reporters—on Lloyd Flanagan’s farm in the green countryside 25 miles from Grand Rapids. Mr. Flanagan, a sturdy man whose family has raised crops and livestock since 1947 on the corner of 4 Mile Road and Lake Murray Avenue, greeted his guests with a smile and a hearty handshake. In this part of West Michigan modesty is a virtue. So Mr. Flanagan listened quietly, shifting his weight and fingering the bill of his worn baseball cap as speaker after speaker extolled the farm’s natural beauty, the family’s good work, and the $580,000 that Kent County raised to buy the development rights to Mr. Flanagan’s 145 acres of good earth, assuring it would be forever used solely for agriculture. At the program’s end, Mr. Flanagan and his wife, Kathleen, who have two sons and a daughter, received a handsome sign commemorating the occasion. “It’s been in the family all these years,” Mr. Flanagan said afterwards of his spread. “I want it preserved. I want to see it stay a farm and see it set up so my son can take over.” The ceremony, gracious in its simplicity, marked the second farm permanently protected by Kent County’s four-year-old Farmland Preservation Program. But what was most significant was the event’s location in a county that not only is among the largest farm producers in Michigan, but also is among the state’s fastest growing and most politically conservative. Here in a region where mixing the basic ingredients of farmland preservation—open ground, government oversight, and public spending—often arouses considerable ire, a new, more supportive attitude about the value of farms, farmers, and farmland is quickly developing. The switch in allegiance is as evident in this part of Michigan as it is in many other regions of the nation where local and state campaigns to protect farmland have surmounted partisan, class, and political impediments to become a powerful, though little-noticed economic and political movement in the United States. Voters across Michigan are being asked to reach into their pockets to increase property taxes to pay for conserving farmland. The results are mixed. Lapeer County voters, for instance, turned down a property tax increase this past Tuesday that would have conserved thousands of acres of farmland and open space in that rapidly growing region. Two years ago, though, voters in Acme Township, east of Traverse City, and in Ada Township, in Kent County, approved tax increases to protect farmland. Three years ago, voters in the Ann Arbor area approved a 10-year property tax that will fashion a “greenbelt” around that city. And this coming November, voters in Leelanau County, west of Traverse City, have the opportunity to approve the state’s first publicly financed countywide farmland preservation program. Coast to Coast Though the nation’s farmland protection efforts also include enacting new zoning rules, taking steps to enhance farm profitability, and enforcing state right-to-farm laws in order to help farmers stay in business, paying farmers to permanently set aside land solely for agriculture is seen as far and away the most effective solution to farmland loss. The reason? “It’s voluntary,” said Eric Larson, executive director of the San Diego County Farm Bureau, who’s working to establish a farmland protection program in southern California, in one of the nation’s largest farm counties. “The other important element is it doesn’t cost much. It’s much less expensive than building roads and sewers and all the other costs that come out of land development.” According to state and federal agriculture departments, this year alone Pennsylvania, Maryland, and New Jersey will spend $386 million on farmland preservation. The number of local land trust organizations, institutions critical to farmland protection, grew to 1,537 in 2003, according to the Land Trust Alliance, 324 more than in 1998. The Trust for Public Land, a national land conservancy, found that since 1994, 384 local and state ballot measures to protect farmland have been put before voters; 312, or 81 percent, were approved. “We’re seeing farmland conservation initiatives approved by voters by equal margins, usually more than 60 percent, in counties carried by George Bush, and counties carried by John Kerry,” notes Will Abberger, the associate director of conservation finance based in the Trust for Public Land’s office in Tallahassee, Florida. “This is not, by any stretch, a partisan issue at the local or state level.” More than an Annoyance But as any planning official who’s put their toes in the farmland conservation pond knows, nothing happens without convincing the producers themselves to also wade in. In the 1990s, as Kent County grew twice as fast as the state, adding 7,400 new residents a year, it dawned on farmers that the effect of rapid development was becoming more than an annoyance. While farmers understood that growth increased their land’s value—a powerful motivation for allowing such development to continue—it also congested rural roads, sprouted subdivisions on the edges of fields, and produced enough general clamor to impede farmers’ ability to efficiently participate in a countywide farm economy that supported 318 commercial farms, 4,500 farm-related jobs, and $150 million in annual farm sales. “It’s happening very fast,” Mr. Flanagan said. “They just built an elementary school out here in the country.” “It’s just getting harder and harder with all the growth to farm around here,” added Jay Hoekstra, a planner with the Grand Valley Metro Council, the regional planning agency. Though several popular farmland conservation measures are available in Michigan and in Kent County—agricultural zoning, farm profitability enhancement programs, Michigan’s right-to-farm statute, and a state farmland property tax reduction program—the tool of choice in Kent and in many other Michigan counties is purchasing farmland development rights. Four years ago, United Growth of Kent County, a civic organization affiliated with Michigan State University, played an influential role in convincing the Kent County Board of Commissioners to approve a county-sanctioned program. No Longer Wacky Until 1994, when Peninsula Township, north of Traverse City, established the Midwest’s first local program, the idea of buying and selling such rights and drawing up conservation easements was considered a wacky idea, appropriate for the coasts, but not considered palatable or needed in the heartland. That’s no longer the case. Kendall and Kane counties in Illinois have established programs, as have two towns in Dane County in Wisconsin. Michigan now has six publicly-funded township programs and the potential in Leelanau County to establish the first county-financed farmland conservation program. Meanwhile Kent County, along with some of its townships, has among the most active farmland preservation programs in the Midwest. Some 112 families in 12 townships have submitted applications for funding to preserve more than 8,000 acres of farmland. Nearly $3 million has been raised from foundations, state and federal farmland preservation programs, local donors, Ada Township taxpayers, and the landowners themselves. All told, efforts in Kent County have amassed enough money to conserve 700 to 750 acres at the going rate of roughly $3,500 to $4,000 per acre. Perhaps two more farms, including one owned by a neighbor of Mr. Flanagan, are likely to be preserved before the end of the year. “I can tell you there is a lot of interest here in preserving farmland,” says Kendra Wills, a land use educator at Michigan State University who staffs the Kent County Agricultural Preservation Board. “I get at least one call a week from a farmer asking about the program.” A Pro-Preservation Slate Farmers tend to be suspicious even though the farmland purchase program is becoming more familiar. “It takes some time, but I’ve been talking to a lot of farmers here. More are interested than they’ve ever been in this program,” observes Mr. Flanagan. A more important critic is the land development community, led by local homebuilder and realtor organizations, which view farmland conservation as an intrusion on the free market and a way for taxpayers, in the words of the Grand Rapids Association of Realtors, to “foot the bill to permanently preserve land they have no access to.” The resistance has convinced the Kent County Commission not to invest any of its general funds in farmland conservation. But a new farmland preservation advocacy organization, co-chaired by a prominent farmer, formed in May. The group, Citizens for Kent County Farmland and Open Space Preservation, promotes county investment in farm conservation, and supports a slate of county commission candidates that want to spend public money on farmland and open space protection. “We are not an outside group with a secret agenda,” explains Rob Steffens, the co-chair and a fourth-generation fruit farmer from Sparta Township. “We simply feel that over the long haul, urban sprawl will destroy the character of Kent County and have huge negative consequences for future generations living here.” This is Part one of a three-part series on farmland preservation programs across America. To read the rest of the series, please click on the page numbers at the top of this article Keith Schneider, a journalist, is editor and director of new program development at the Michigan Land Use Institute. A longer version of this article was published in the Summer 2006 issue of the Planning Commissioners Journal. The full article is available to order and download at: www.plannersweb.com/ag.html. Reach Keith at keith@mlui.org.

All of this is part of a national trend. From New England to southern California, Florida to Washington State, and countless places in between, local planning officials are teaming up with elected leaders, non-profit conservancies, and the farm community to spend nearly $500 million annually to preserve more than 400,000 acres of orchard and crop land, according to farmland conservancies.

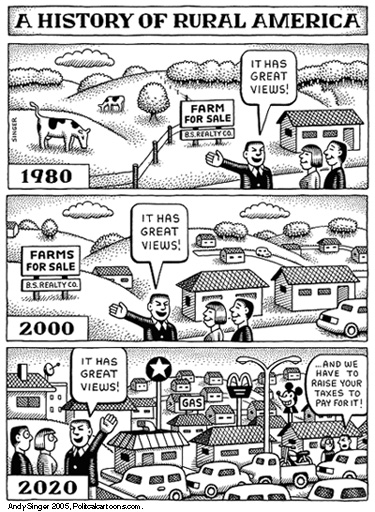

Neither is it in Kent County. Here as in most of the other regions concerned about the loss of farmland, a tide of new homes is pushing out of a nearby metropolitan area—in this case Grand Rapids, the state’s second largest city—and steadily topping one ridge after another. Here that tide is now approaching this bedroom and farm community of 4,000. The spread of new homes and families, and their attendant needs—wider roads, longer sewer and water lines, new schools and retail developments—is becoming an ever heavier tax burden for the county’s 594,000 residents. Rampant construction also has intruded on Kent County’s view of itself as a largely rural, quiet, almost changeless place apart from everywhere else.

First implemented by Suffolk County, N.Y., in 1974, a purchase of development rights program pays farmers a substantial per-acre fee that amounts to the difference in value of the land as farmland and its value as land sold for new residential and business development. In exchange for selling such “development rights,” farmers attach a permanent conservation easement to the deed that puts the ground off limits to anything other than farming.

Still, there is unease in and out of the farm community.